As usual, the last year has seen its fair share of trade mark disputes involving fashion brands. Perhaps the highest profile case was Adidas AG v Pacific Brands Footwear Pty Ltd (No 3),1 in which the presiding judge had the unenviable task of deciding whether nine separate examples of sports shoes with four stripes were, or were not, deceptively similar to the applicant’s trademark, which involved the use of three stripes.2 In this article, we take a look at some of the other cases.

Louis Vuitton

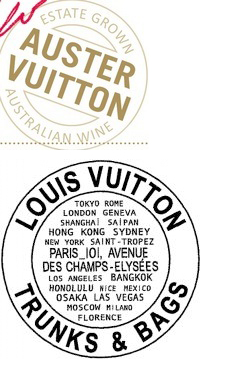

First out of the starting gates is Louis Vuitton Malletier, with two cases. The first3 came before a delegate of the registrar in June 2013. While the notice of opposition nominated a number of grounds, the opponent only proceeded under the s 60 ground at the hearing.

The marks in issue were as shown in Fig 1.

Figure 1

|

The applicant’s mark was for wines and wine-based beverages. However, the delegate found that the reputation of the opponent’s mark was such that the use of the first would nonetheless be likely to deceive or cause confusion. The opposition was successful on the s 60 ground. It is noted that there were no submissions filed on behalf of the applicant and there was no appearance by or for the applicant at the hearing. However, a Mr Wang of the applicant attended the hearing as an observer.

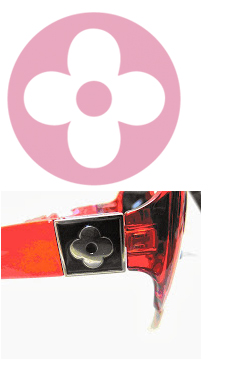

The second case4 involving Louis Vuitton Malletier was the subject of a judgment by Jessup J in the Federal Court in September 2013. In that case, the respondent was found to have infringed the flower logo trade mark of the applicant, Louis Vuitton Malletier, by using a deceptively similar mark on the arms of its sunglasses (Fig 2).

Figure 2

|

However, in this case, the court held that the respondent’s “LOUIS V” trade mark was not deceptively similar to “LOUIS VUITTON”. The court was not impressed that Louis Vuitton sought to rely on a two-paragraph affidavit from its solicitor, where each paragraph began with the words “I am instructed” and did not consider that this evidence established that the trade mark was “notoriously so ubiquitous and of such long standing that consumers generally must be taken to be familiar with it and its use in relation to particular goods”.5 This level of reputational evidence, the court said, was necessary to include reputation in the assessment of the consumer’s imperfect recollection for the purposes of s 120(1).

It is important to remember that the fame of a brand has actually been its downfall in this comparison in the past.6 It is unclear whether, if the evidence had been sufficient, this finding as to lack of deceptive similarity would have been any different.

It is also interesting to note that his Honour felt that he could take the applicant’s reputation into account for the purposes of its claims under the Australian Consumer Law. He found that a consumer would be misled by both the “LOUIS V” trade mark and the flower mark, so the applicant succeeded on both those claims.

Stella McCartney

Stella McCartney Ltd succeeded in its opposition to the registration of “ST ELLA – NEW YORK” under s 44.7 This case has received some publicity, due to a submission by the opponent’s representative that the marks had an aural similarity owing to the tendency for “persons, particularly in Australia, to be lazy in their pronunciation”.8 Reading the full reasons, however, which are very detailed, Delegate Iain Campbell Thompson was really persuaded by the visual similarity of the two marks, which was as a result of the way in which the applicant had chosen to represent its mark (Fig 3).

Figure 3

|

This case was not an obvious one of an applicant trying to take advantage of a registered mark, with one of the applicant’s founders and directors having the forename “Stella”. However, the opponent’s registered trade mark was in normal uppercase typed font. When rendered in the italic script of the applicant’s mark, the two marks were held to strongly resemble each other.

The order of the letters was the same, and it was held that “the ‘crossbar’ of the alphabetical letter “t” extends across the space between the abbreviation “St” and the word “Ella”, which gives the initial impression that the abbreviation “St” and the word “Ella” are (and form) a unity”.9

Bugatti GMBH

While not as famous a fashion house as the last examples, German men’s outfitter Bugatti GmbH (not to be confused with the French luxury automobile marque) has been involved in two actions in Australia in the last year. The first was an opposition and the second involved proceedings for trade mark infringement, both in respect of the trade mark “BUGATCHI UOMO”.

The first case to be decided was Bugatti’s application in the Federal Court10 for infringement against the owners of a menswear retail business in Melbourne that imported and sold clothing and accessories through a retail outlet called “Bugatchi Uomo”. Justice Tracey ruled that in the context of clothing in class 25, both BUGATCHI UOMO and BUGATCHI alone were deceptively similar to the applicant’s BUGATTI word trade marks, which had also been registered in class 25 (and in several other classes in respect of accessories, textiles and textiles goods, and the retailing of them).

Figure 4

|

In that case, the court held that there was visual and aural similarity between the two marks.

In the hearing of Bugatti GmbH’s opposition11 to Canadian company Bugatchi Uomo Apparel, Inc’s international application to register the word mark “BUGATCHI UOMO” in class 25, the delegate requested and received written submissions from the parties on the relevance of that judgment to the opposition proceedings.

Delegate Heath Wilson felt that he was bound by the decision of the Federal Court that the marks “BUGATTI” and “BUGATCHI” were deceptively similar when used in relation to clothing and that the addition of the word “UOMO” did not “serve to dissolve any confusion which might otherwise arise”.12

The delegate nevertheless went on to consider in his judgment the aural and visual similarity of the marks, with the result that the opponent was successful in establishing its opposition on the s 44(2) ground. The delegate found that, on the evidence, the applicant failed to make out either the exception for honest concurrent use (s 44(3)(a)) or other circumstances (s 44(3)(b)).

1 Adidas AG v Pacific Brands Footwear Pty Ltd (No 3) (2013) 103 IPR 521; [2013] FCA 905; BC201312738. See the article by Sébastien Clevy in this issue of the Australian Intellectual Property Law Bulletin.

2 He found that only three of the nine were deceptively similar.

3 Louis Vuitton Malletier v WinWorld Australia Pty Ltd [2013] ATMO 46. See A McDonald, L Eade and L Lennon “Louis Vuitton Malletier v Sonya Valentine Pty Ltd: s 120(1) doesn’t give a damn about Louis Vuitton’s reputation” (2013) 26(6-10) Australian Intellectual Property Law Bulletin 131.

4 Louis Vuitton Malletier v Sonya Valentine Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 933; BC201312983.

5 Above, n 4, at [34], quoting from the judgment of the Full Court in CA Henschke & Co v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd (2000) 52 IPR 42; (2000) AIPC 91-640; [2000] FCA 1539; BC200006518.

6 Mars Australia Pty Ltd v Sweet Rewards Pty Ltd (2009) 81 IPR 354; [2009] FCA 606; BC200904981. See also C Logan “Mars fail to get up in get up case: Maltesers rolled down the aisle and out of court” (2009) 22(3) Australian Intellectual Property Law Bulletin 46; C Logan “Maltesers rolled again on appeal” (2010) 22(7) Australian Intellectual Property Law Bulletin 140.

7 Stella McCartney Ltd v Wong Kwaid Hua [2013] ATMO 96; BC201316949.

8 Above, n 7, at [51].

9 Above, n 7, at [70].

10 Bugatti GmbH v Shine Forever Men Pty Ltd (2013) 103 IPR 574; [2013] FCA 1116; BC201314200.

11 Bugatti GmbH v Bugatchi Uomo Apparel Inc (2013) 104 IPR 348; [2013] ATMO 102; BC201316316.

12 Above, n 10, at [41].