On 15 October 2021, the Supreme Court of NSW dismissed challenges to the COVID-19 vaccination requirements for certain workers imposed under NSW public health orders. The two sets of proceedings in Kassam v Hazzard; Henry v Hazzard [2021] NSWSC 1320 were commenced by 10 plaintiffs who refused to comply with the mandatory COVID-19 vaccination requirements imposed by the:

- Public Health (COVID-19 Aged Care Facilities) Order 2021 (NSW) (Aged Care Order);

- Public Health (COVID-19 Vaccination of Education and Care Workers) Order 2021 (NSW) (Education Order); and

- Public Health (COVID – 19 Additional Restrictions for Delta Outbreak) Order (No 2) (Delta Order No 2).

(collectively, Orders)

The plaintiffs largely contended that the Orders violated their rights to bodily integrity and privacy, were unconstitutional, were discriminatory, and represented a breach of natural justice and procedural fairness.

The decision represents the first major challenge to mandatory COVID-19 vaccination requirements in an Australian or State Court. The decision reinforces validity of the Orders as “reasonably necessary to protect public health and safety”.[1]

The ‘contested’ Public Health Orders

The case called into question the validity of mandatory COVID-19 vaccination requirements imposed by the Orders as they existed at the relevant time.

Aged Care Order

The Aged Care Order was made on 26 August 2021 and came into effect on 17 September 2021. The order was the subject of challenge by the plaintiffs:

- Clause 5 imposed restrictions on aged care workers (broadly speaking) from entering or remaining on the premises of a residential aged care facility unless they have received at least 1 dose of a COVID-19 vaccine;

- Clause 6(1) contained a direction from the Minister that on or after 9.00am on 31 October 2021, health practitioners or students “must not enter or remain on the premises of a residential aged care facility unless the person has received 1 dose of a COVID-19 vaccine”.

Education Order

The Education Order was made on 23 September 2021 and commenced immediately. The order was the subject of challenge by the plaintiffs:

- Clause 4 imposed restrictions on education and care workers (broadly speaking) from entering or remaining in schools and education and care facilities after 8 November 2021, unless they have received 2 doses of a COVID-19 vaccine or have been issued with a medical contraindication certificate.

Delta Order No 2

The Delta Order No 2 was made on 20 August 2021 and applied from that date until 10 October 2021.

The Delta Order No 2 imposed restrictions to persons living within a “local government area of concern” and in particular:

- Clause 4.23 imposed restrictions on relevant care workers (defined broadly to mean workers in early education and care and disability support) who live or work in an area of concern, from entering or remaining in their place of work unless they received 1 dose of the COVID-19 vaccine or had been issued with a medical contraindication certificate;

- Clause 4.3 imposed similar restrictions on persons from leaving a local government area of concern unless they were an “authorised worker” who has had at least 1 dose of a COVID-19 vaccine or had been issued with a medical contraindication certificate;

- Clause 5.8 imposed further restrictions on a person whose place of residence was in an area of concern from entering or remaining on a construction site in Greater Sydney unless they had:

- Received 2 doses of a COVID-19 vaccine, or

- 1 dose at least 21 days ago or otherwise coupled with a test in the previous 72 hours, or

- A medical contraindication certificate.

The Plaintiff’s Legal Arguments

The 4 plaintiffs in Al-Munir Kassam v Bradley Ronald Hazzard were affected by the Delta Order No 2 and relied upon various grounds to establish its invalidity including:

- That the Minister did not undertake any real exercise of power in making the order;

- That the order is either outside the power conferred by s 7 of the Public Health Act 2010 (NSW), or represents an unreasonable exercise of that power because of its effects on fundamental rights and freedoms;

- The matter in which the order was made was manifestly unreasonable for reasons beyond its supposed violation of the right of bodily integrity;

- The order was unconstitutional, namely that it was invalid by s 51(xxiiiA) of the Constitution because it had the effect of imposing a form of civil conscription by requiring unvaccinated persons to obtain a COVID-19 vaccine; and

- That the production of vaccination evidence under the order was inconsistent with the federal Australian Immunisation Registered Act 2015 (Cth) (AIRA), which governs the record, use and disclosure of health information, by s 109 of the Constitution.

The 6 plaintiffs in Natasha Henry v Brad Hazzard were affected by the Delta Order No 2, Aged Care Order and Education Order and relied upon the following grounds to the invalidity of the Orders:

- The Orders were beyond the scope of s 7 of the Public Health Act 2010 (NSW) on the basis they violated a number of fundamental individual rights and freedoms, including the right to freedom of movement, right to work, right to privacy in relation to collection, use and disclosure of health information contrary to health privacy legislation;[2]

- The Orders were made for an improper purpose, namely that the Minister failed to consider the rights of unvaccinated persons which were engaged by the exercise of his discretion under s 7 of the Public Health Act 2010 (NSW);

- The Orders were administrative decisions which affected the rights, interests and legitimate expectations of the plaintiffs and thus the Minister was obliged to but failed to afford them natural justice and procedural fairness;

- The Minister acted unreasonably where the Orders interfered with fundamental rights; and

- The Orders were unconstitutional and amounted to a form of civil conscription proscribed by s 51(xxiiiA) of the Constitution.

The Decision

The proceedings were dismissed after Chief Justice at Common Law Beech-Jones rejected all of the asserted grounds of invalidity raised by both sets of plaintiffs.

Breach of Fundamental Rights

His Honour observed that in the absence of a Bill of Rights at the federal or state level in NSW, the rights that may have been infringed upon had to derive from those rights already recognised at common law.

Put simply, it was determined that the requirement to get a COVID-19 vaccine in relation to certain jobs under the Orders did not violate a person’s right to bodily integrity. Rather, His Honour considered that the object of the Orders was to impede on a person’s freedom of movement which has consequential effects on a person’s ability to work. While freedom of movement is undoubtedly important, it is not a positive right. Moreover, it was observed that s 7 of the Public Health Act 2010 (NSW) allowed the Health Minister to implement actions and directives upon consideration of reasonable grounds that a situation has arisen that is, or is likely to be, a risk to public health. The whole purpose of section was thus clearly directed to limit freedom of movement, sometimes severely.[3]

Similarly, the protection against discrimination is not a positive right recognised by the common law and the restrictions imposed on unvaccinated persons could not be held discriminatory.

The plaintiffs also sought to rely upon the dissenting judgment in Jennifer Kimber v Sapphire Coast Community Aged Care [2021] FWCFB. In particular, they relied on various passages in the Deputy President’s judgment to the effect that “vaccine mandates” embodied in the various public health responses to COVID-19, amount to a form of coercion that violates a person’s right to bodily integrity.[4] However, His Honour opined that the function of the Court is to determine the validity of the Orders and not to determine whether the Orders should have been made, which is for the political process.

Constitutional Argument

His Honour further rejected the constitutional argument about civil conscription and asserted inconsistency with the AIRA. Section 51(xxiiiA) of the Constitution confers legislative power on the federal parliament to make laws with respect to “[t]he provision of maternity allowances, widows pensions, child endowment, unemployment, pharmaceutical, sickness and hospital benefits, medical and dental services (but not so as to authorise any form of civil conscription), benefits to students and family allowances …”

His Honour held that nothing in the text or structure of s 51(xxiiiA) gives rise to an “implied constitutional right of individual patients to reject unless consented to vaccinations”.[5] Further, even if the Orders imposed a form of civil conscription, which they do not, s 51(xxiiiA) does not bind the States and would not be rendered invalid by its operation.

In addition, his Honour briefly held that any purported inconsistency with the AIRA was groundless and without substance, as nothing in the AIRA conflicted with the obligation to disclose vaccination evidence in the circumstances addressed in the Orders.[6]

Significance of Decision

The decision represents the first major challenge to mandatory COVID-19 requirements in an Australian Court. Whilst the decision does not alter compliance with mandatory vaccination requirements imposed under the Orders, it is likely to guide any future challenges.

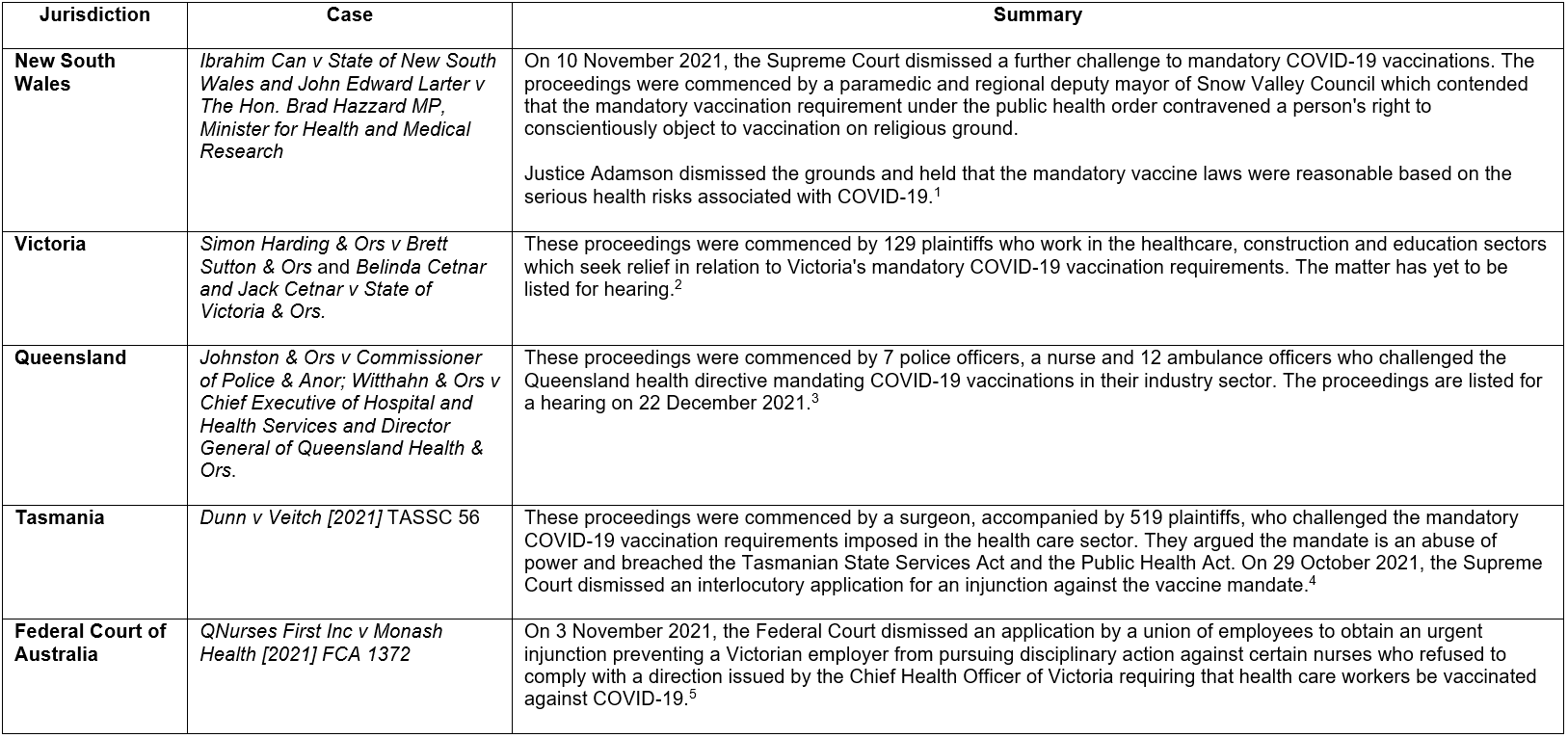

There are currently several challenges against State-ordered mandatory COVID-19 vaccinations which have been decided since this decision and others which are pending before Courts in NSW and other Australian jurisdictions.

Takeaway

It should be noted that the COVID-19 vaccination requirements imposed under the Orders referred to above have since been repealed and amended. However, the decision serves as a reminder regarding compliance with any existing mandatory COVID-19 vaccination requirements under the current public health orders which apply to certain workers.

Please contact our team for assistance or to discuss how the mandatory COVID-19 vaccination requirements affect you.

[1] Kassam v Hazzard; Henry v Hazzard [2021] NSWSC 1320 [206].

[2] Privacy Act 1998 (Cth); Health Records and Information Privacy Act 2002 (NSW); Australian Immunisation Register Act 2015 (Cth).

[3] Kassam v Hazzard; Henry v Hazzard [2021] NSWSC 1320 at [70].

[4] Jennifer Kimber v Sapphire Coast Community Aged Care [2021] FWCFB at [115] – [129].

[5] Kassam v Hazzard; Henry v Hazzard [2021] NSWSC 1320 at [276].

[6] Ibid [292].

[7] Ibrahim Can v State of New South Wales (2021/00265124); John Edward Larter v The Hon. Brad Hazzard MP, Minister for Health and Medical Research (2021/00259688).

[8] Simon Harding & Ors v Brett Sutton & Ors (S ECI 2021 03931); Belinda Cetnar and Jack Cetnar v State of Victoria & Ors (S ECI 2021 03569).

[9] Johnston & Ors v Commissioner of Police & Anor; Witthahn & Ors v Chief Executive of Hospital and Health Services and Director General of Queensland Health & Ors [2021] QSC 275.

[10] Dunn v Veitch [2021] TASSC 56.

[11] QNurses First Inc v Monash Health [2021] FCA 1372.

Article prepared by: Sarah Cappello, Partner, Joey Tass, Senior Associate, and Margaret Gotsopoulos, Graduate.